Photos - Olivia Renouf

Cable knit inspired by Thrity teaching

Model – Derya Parlak

My grandmother has never ceased to provide immense warmth and comfort to all her kin during the time I've known her. From the perspective of my personal iconography, Thrity Lakdawalla is the equivalent of a divine matriarchal creature - this round deity with wide features and large, competent hands. The abundance of spirit and knowledge that I've inherited from her is of unquantifiable value. It has shaped and moulded this textile practitioner before you today.

In order to retain some objectivity, the following is an account from my life that I will recite in third person.

It was the summer of 1996 and a young Areez was playing with his newly rescued rabbit on a terrace during a stay at his family’s holiday home in India. He found very little to do that day, because his parents and sister had left on a small weekend excursion to visit Zoroastrian fire temples along the coast of Gujarat. He did not speak much Gujarati or Farsi at that point in his life, so English was his first and only spoken language. India was often revisited at an attempt to ground his family’s nomadic Persian roots and maintain connections with extended Parsi relatives.

By the age of seven, Areez realized that he wasn’t like many other boys around him; he didn’t have much interest in playing games like cricket or football in the same way that they did. And they weren’t interested in books on animals and plants in the same way that he was. Everywhere he looked, he saw things that these big patriarchal figures were doing, including prescriptions on how to act and feel. Areez wasn’t nearly interested or good enough at pretending to be, especially on that day. So it seemed, there was no role model or figure in his life he knew to have embodied qualities that were not traditionally suited to a boy of seven years. Curiosity, softness and patience weren’t quite what the folks expected to see in him.

So Areez peered into the sea, past his cousins from their sea-facing balcony at the beach. They were playing football and building sandcastles, but then crushing them like giants – gleeful olive-skinned children flanked that small coast along a greater Indian Ocean – with Persia, once home to their kind, somewhere across that very sea. He would’ve normally been coaxed to join them but Areez hadn’t been paid much attention that day. The sun was at its height and the tide, he thought, was low enough to collect hermit crabs.

Photos - Olivia Renouf

Cable knit inspired by Thrity teaching

Model – Derya Parlak

That summer, Areez found that his pet rabbit Clementine was a better playtime companion. This was until he unwittingly led her down the stairs, where she meekly burrowed under the villa’s foundation beams. After a strenuous search through the bougainvillea, he gave up. And so he returned upstairs, disheartened. Anxious and now restlessly thumping his little back against an old wooden beam on the second-floor landing, his grandmother began to approach. A brief description of Thrity: her hair was a shade of dark brown back then, with a few streaks of grey – all contained in curls that fell down to (but not beyond) her shoulders. Her figure was already round and full back then, but robust and less fragile than now. She wore a loose pale blue frock with a square neckline that was trimmed with homemade lace. Thrity leaned against the balcony rail across from her grandson; he perfunctorily smiled but then resumed a facial grimace he often wore, looking down at nothing in particular.

Thrity asked him why he wasn’t playing with the kids down by the seashore. He shrugged and dropped his head even lower. She ignored his insolence by then asking what he wanted to do. He shrugged again, a more exaggerated and deliberate offence to an elder that his father would’ve told him off for, had he witnessed it. But Thrity was more intuitive and sympathetic to the kind of behavior her grandson was displaying. She stepped closer and moved behind him – wrapped her arms around his little shoulders, hands drooping over his torso. He leaned back automatically, with his head pressed against her chest. She bent down and kissed his crown, saying “Come on now Ari, let’s have some tea. No use in waiting for those fools.”

There was an old outdoor stove in the corner of their balcony, which she ignited to a medium flame and placed an almost-full enamel teapot of water, which Areez was asked to fetch from the well. As it simmered, she opened a large tin of Darjeeling tea and loosely heaped teaspoon after teaspoon (three) that slowly infused in the water. He watched her from a meter away, sitting on a stool under the cascading bougainvillea canopy where there were sets of cane stools and two round tables. She briefly stepped inside and retrieved a tray with two cups & saucers, a pot of sugar and a jug of fresh milk from the neighbour’s goat that morning. Placed it on the table further away from him, Thrity then stepped closer to his table and placed a long grey leather pouch next to him. He looked at it and saw that the zip was partially opened. The bag contained several pairs of long wooden needles and balls of fluffy yarns coloured pale green, yellow and creme. His mood was still sullen, but slightly uplifted by the soothing combination of maternal care and a mild material curiosity.

Thrity clinked about with cups, saucers and pots as he dissected several pink bougainvillea blossoms in the partial sunlight that they were under. She looked up and away for a moment, before offering him a cup and saucer with a teaspoon tucked under its arm. It was then filled with a hot stream of bark-toned tea, followed by a marbling swirl of fresh milk and a heaped teaspoon of lumpy sugar. The same for herself, but with a less-milk-and-more-tea grown up ratio.

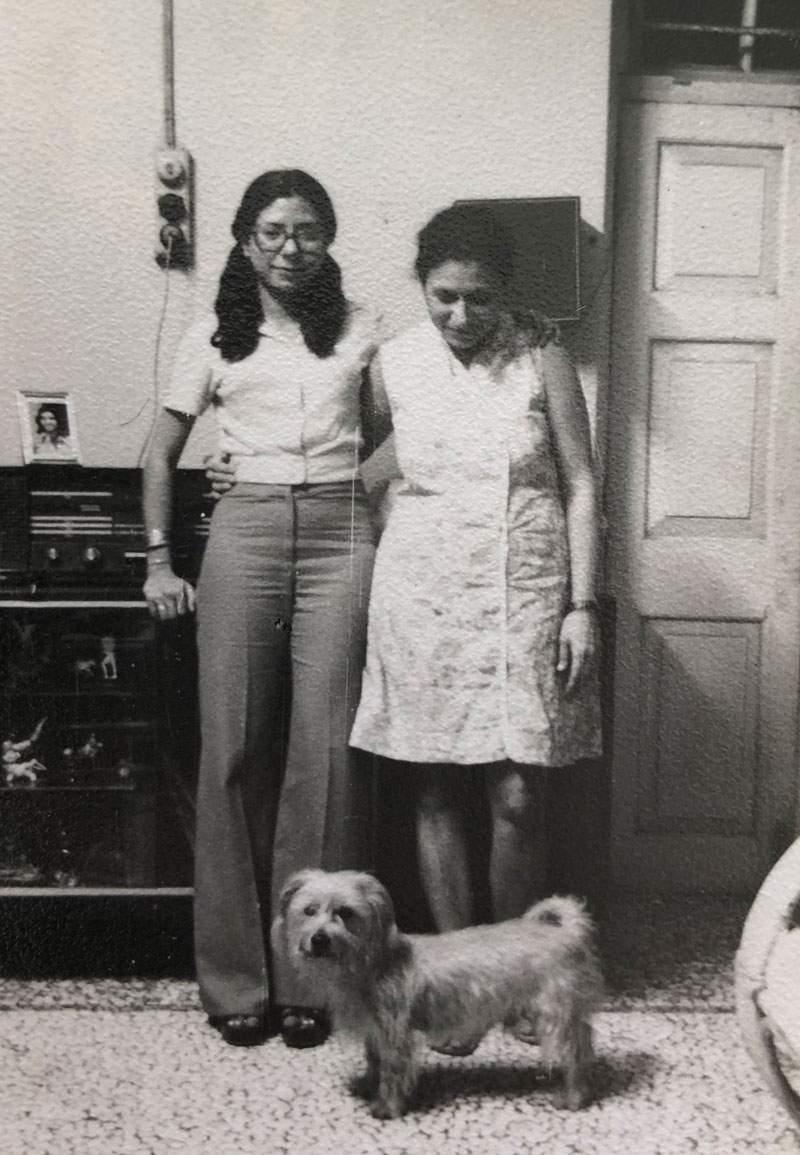

Yasmin and Thrity 1972

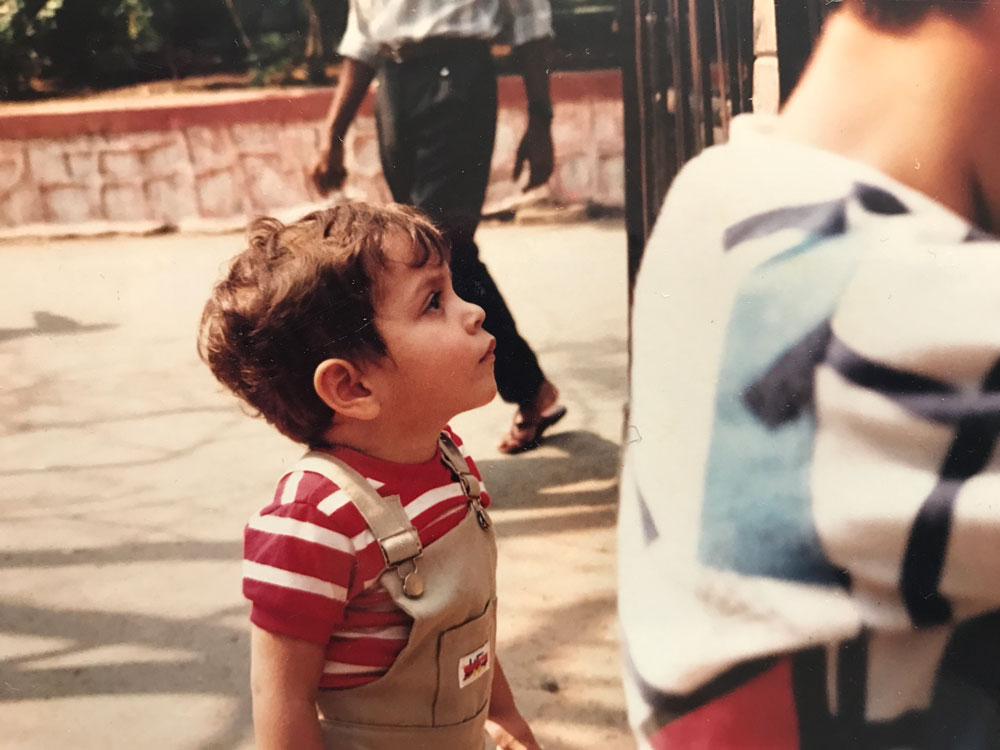

Areez at a play park near his maternal family's Parsi Colony home in Mumbai (which was still called Bombay at the time). 1993.

Thrity with Areez in *Udwada, 1991.

*Udwada is a small village on the coast of Gujarat 20km from where the first Zoroastrian immigrants arrived by sea from Persia 10 centuries ago. A pilgrimage site, hosting a fire that was transported by hisancestors by sea and still kept aflame at Iranshah Temple.

She sighed, sat down and shuffled closer to him, within easy reach of their mysterious vinyl pouch. As they sipped on their sweet hot tea, he heard the squawk of a seagull. She asked, “So what did you want to do this afternoon? The others are hours away. They might even call to say they’re staying the night in Navsari. Especially if your mother has her way –she always loved that village, ever since she was a little girl.”

He shrugged again, but eventually admitted, “No idea. Suppose I’ll have to join Farzan and all the boys for their bonfire tonight.” Thrity responded, “Well you don’t have to do anything, you know. If you wanted, we could do something up here. Just you and me,” to which he looked at her blankly – “O.K. Clementine is still hiding, she probably hates me because I held her too tight.”

“Well I’m not sure, perhaps she’ll come back out when the sun sets in a few hours? I’d help you look for her but – my knee… and I have the feeling she’ll probably just run off again if you force her in.” At that point he let out a whinny, the way little boys only do in the private presence of their grandparents, and pushed his upper body under her shoulder with her left arm cocooning his side. “Now, now –let me show you something. It may seem like I’m teaching you a boring old skill. But that doesn’t mean it’s useless. Okay?” He nodded, with his head still buried under her arm.

She pulled out a few things from the pouch and set them out on the table, returning a few others back inside. Their essential tools were revealed to be four sets of needles: a pair of 5mm cane needles and a 4mm grey aluminum pair. The latter had already grown a young dusty green ribbing line, linked to a big ball of yarn. There were a few other small bundles of yarn that spilled out. He turned his head around in curiosity and picked up a ball of charcoal grey wool, looking for its open end –finding it and then twirling it around his middle and index fingers.

Thrity smiled and let out a sigh – “Okay. So you know how I made your sister that scarf last year and how it unraveled after you two played at the park? And then remember how I fixed it?” –Areez nodded. “Well, that’s what is so lovely about knitting. We make things, they come apart and then we fix them – by tracing steps that lead back to those original lines. We must always preserve the things we make with our hands, because they mean so much more than the things we buy.” He kept looking down at his fingers, now tangled in a great mess of wool. She picked up the pair of 4mm needles with the green ribbing, punctuated her posture and unraveled a meter or so of yarn. Then, Thrity began a new row to instruct how a knit was made and then, how a purl is it’s exact mirroring stitch. Areez watched and learned something that he’d never forget.

Areez and his older sister Delzin in Muscat 1992

Areez’s practice is now divided between his studio in Auckland, New Zealand and his ancestral home in Mumbai, India. His current placement in Mumbai serves as an ideal setting for investigative projects on Parsi craft practices and cultural research on the diaspora of an ancient Zoroastrian community that he was born into. The work aims to revive and reappropriate certain aspects of his heritage that have informed his work as a maker.