My poem ‘The Jersey’ was written some months after my father died. I thought I wouldn’t write about his death – it seemed something I couldn’t go near – but seeing a photograph of him in his old green jersey gave me a way in.

A long time ago a friend

offered to knit me a jersey.

Because she was a busy person

we agreed she’d do it

when she found time.

A year went by and I moved away

from Dunedin (this was one of the reasons

for the jersey — it was very cold

and I didn’t have enough

warm clothes).

I did buy a lot of second-hand coats

that year, and made do

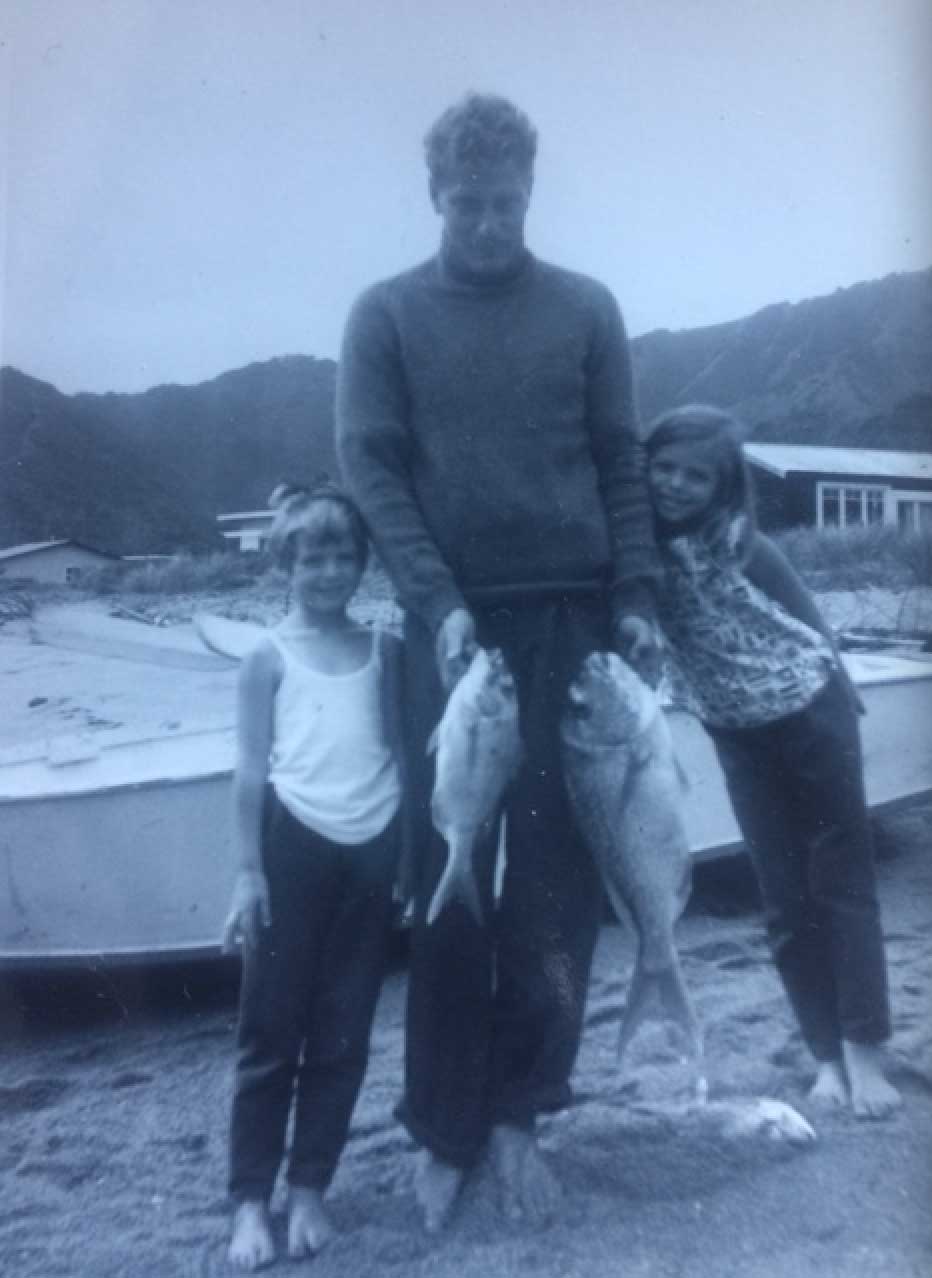

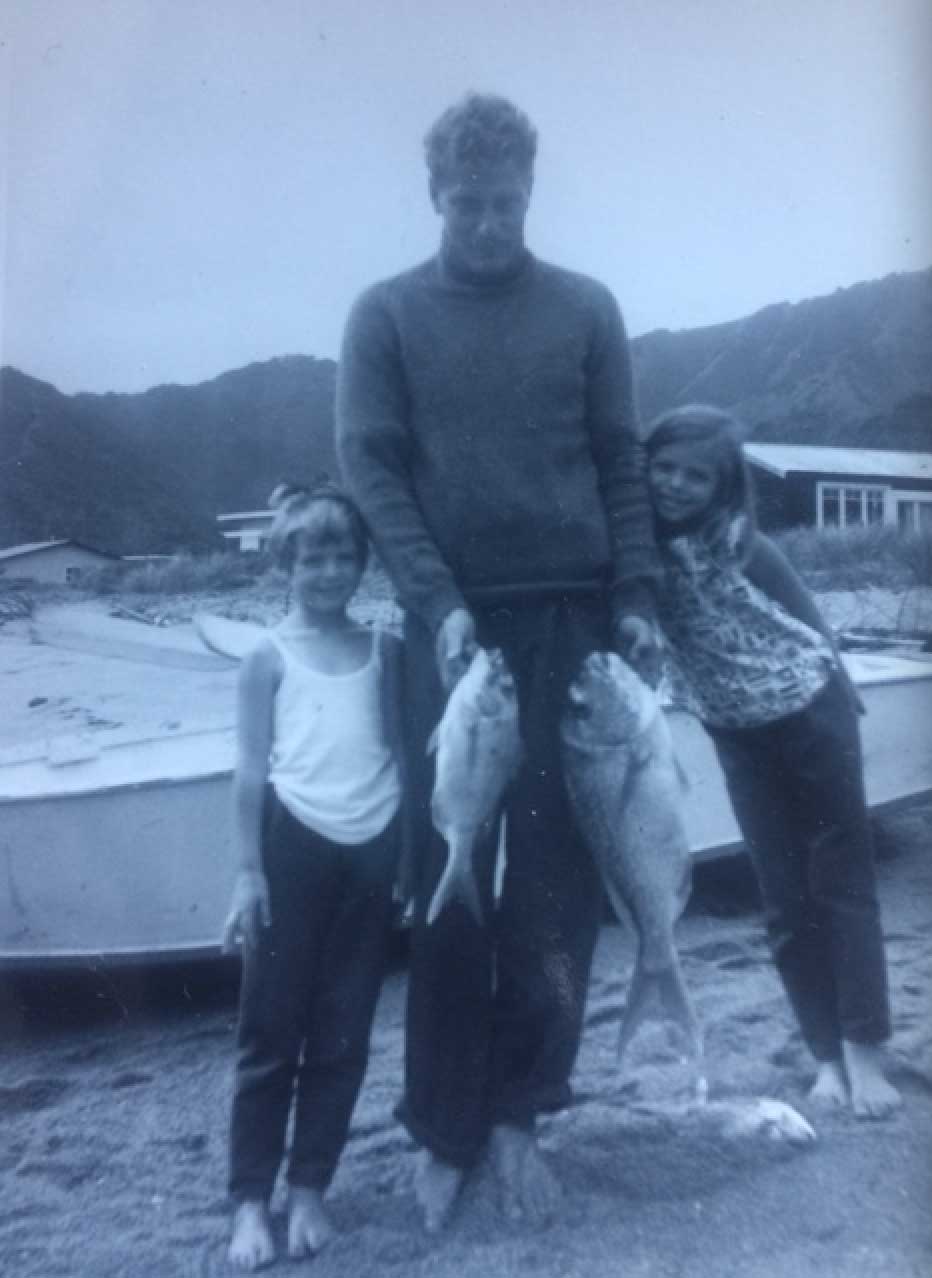

with my father’s old green fishing jersey

— one he’d been wearing the day he caught,

then lost, an enormous snapper

off the wharf at Golden Bay.

I was with him then

and remember the excitement

as we watched the fish

swirl up towards the surface

then the disbelief as the hook

came free and the great shape moved

away and down and down

until it became water

once more.

The jersey was a fine one

but rather large, as my father had been.

Fifteen years later the new jersey arrived

wrapped in brown paper and crammed into

our letterbox. It was a beautiful thing —

full of colour and texture. I am a tall person

but this jersey was made for someone much larger

than myself. Because of its size

and because I loved it but couldn’t wear it

I put it in a cupboard while I thought

about what to do.

*

Then my father died and the world became a stopped

unsteady place.

After a time

I got back to doing the things

I’d done before.

Our son started swimming lessons.

In his class was a child named Lyric.

At the end of each lesson

she and my son floated

on their backs

while the instructor towed them

through the water.

There was a weird stillness about the children

when this happened.

It was as if someone had flicked

the sound off

carving a core of silence

into the pool’s

noise and tumble.

*

I got the jersey out and decided to take it apart.

Because a lot of the wool was mohair and had been knitted

two strands together, it took a very long time.

It was complicated and frustrating and sometimes

I had to take to it with the scissors.

But even then I was grateful.

Please don’t read too much into this.

I can imagine the temptation to see this jersey

as my life — here I was unravelling it (see,

already it’s in balls in a bag on the floor)

ready to fashion into something else —

but it wasn’t like that.

I don’t mean to implicate my friend in this either.

She in no way set out to make anything

that would have to shoulder the responsibility

of metaphor. It was a jersey she knitted

and I am the one who took it apart.

Every evening I knitted peggy squares,

which were the simplest things

I could think of. And I would wear my father’s

pyjamas — lovely striped cotton ones —

the kind of cotton that’s so soft it feels

like silk. My mother bought him these pyjamas

to wear in the hospice

but he never even slipped his arm

into a sleeve.

*

After he died we gave away most of his clothes.

Other men in the family fitted his shirts.

His suits we gave to an organisation that helped

immigrant families. Some things we kept —

a man with one foot two sizes smaller

than the other, no one could ever step

into his shoes.

What do you do with cufflinks

all the little gold and silver bits

clinking in the dish?

His old green fishing jersey was long

gone. I’d never found it after I moved

from Dunedin.

It returned in a dream though.

A dream that came, I think, because of my friend

Mary, who found four boys’ jerseys

in an op shop

in Milton.

She sent these jerseys to our youngest

son. Beautiful jerseys — striped and flecked

in colours you never see now

mostly because children

don’t wear wool much

anymore.

We bemoaned this fact, Mary and I,

and that was when she recalled seeing the jerseys

and vowed to send them.

In the dream, my father’s jersey — very old

and full of holes — was folded

beautifully but belonged

to someone else.

I couldn’t bear to see it on their shelf.

Couldn’t bear to leave it.

I woke, of course, and it

was gone.

*

It’s the closest I’ve come to dreaming

about my father.

When he was ill, I woke one night

when he called my name

but even as I snapped

into consciousness I realised

he was on the other side of town

and I’d manufactured

his need for me.

*

Mary told me that as her mother

lay dying, she made sculptures from sticks

on the lawn outside her window.

All day this daughter

moved about the lawn

placing twigs carefully

on or against each other.

I wish I could have done this.

I wish I could have made something

in the face of my father’s illness.

Instead, it became

a ragged hillside to be crossed,

furious with grief,

wondering at how unfaithful, how

ungrateful, his body seemed.

His illness

unmade me.

I wanted to climb back

inside the arms

of my first, strong, disintegrating

family. It made me fear

for my mother.

I didn’t want

to let her out

of my sight.

*

Through that winter

after my father died

I knitted, and the pile

of peggy squares grew.

I took some pleasure

in laying them out

on the floor

to see how the colours

might go together.

*

For my forty-first birthday

I was given a tea towel

by my friend who had knitted

the jersey.

This tea towel features a

Horse Map of the World.

The horses stand proudly.

There’s the Connemara Pony,

the French Coach, the Shetland

Pony, the Mongolian and Polo

Ponies, Prejvalsky’s Horse, the

Darley Arabian, the Clydesdale

and the Kentucky Saddle, the

Mustang and the Suffolk Punch.

It occurs to me that

out of my knitting

I could make a horse

blanket. Not for one of these

Horses of the World

but for a horse my father rode

at Cape Palliser

in a photograph we have of him

as a young man.

My blanket would keep this horse

warm. It would love

it. The thought of this blanket

would mean this horse

would take my father out

over the roughest tracks

and always bring him

safely home.

Jenny Bornholdt has published ten books of poems, the most recent of which is Selected Poems.

Her poems have appeared on ceramics, on a house, on paintings, in the foyer of a building and in letterpress books alongside drawings and photographs. She has also written two children’s books.

This year (2018) Jenny and her husband, writer/artist Greg O’Brien, are living in the Henderson House in Alexandra, Central Otago. They are wearing a lot of wool.